On the day of my brother’s birth, I woke up in my grandmother’s brass bed to the sounds of a whispered conversation in two different languages, both of which I understood, sort of. My grandmother, my vovó, had already gotten up, and I had the whole double bed to myself. When I say it was a brass bed, I use the term loosely. I know now that brass beds are not always made of brass; some are made of iron or a combination of the two metals. I also know now that brass beds are likely to be hollow, with brass plating over cast iron tubing. Vovó’s bed was hollow, and one of the finials at the foot of the bed was loose. When no one was looking, I would lift it off the bed post and position it on my head so that it looked like a crown. It was too small to be a crown for a grown-up, but I was only five years old. I would stand in front of Vovó’s mirror and pretend to be a queen or a princess. I would be happy.

On the day of my brother’s birth, I didn’t have time to play with Vovó’s finial. I had to get ready for kindergarten, but first I had to deal with the voices coming from the living room. I understood enough of the whispers to know what I was about to be told, and it was what I had been expecting. Of course I was disappointed. I really wanted a sister, but my aunts and older cousins had been experimenting with the wedding-ring trick, tying my mother’s ring to a piece of string and suspending it over her tummy, watching to see whether it swayed from side to side or moved in circles. It definitely did not move in circles. It will be a boy, they said, and everyone except me was happy.

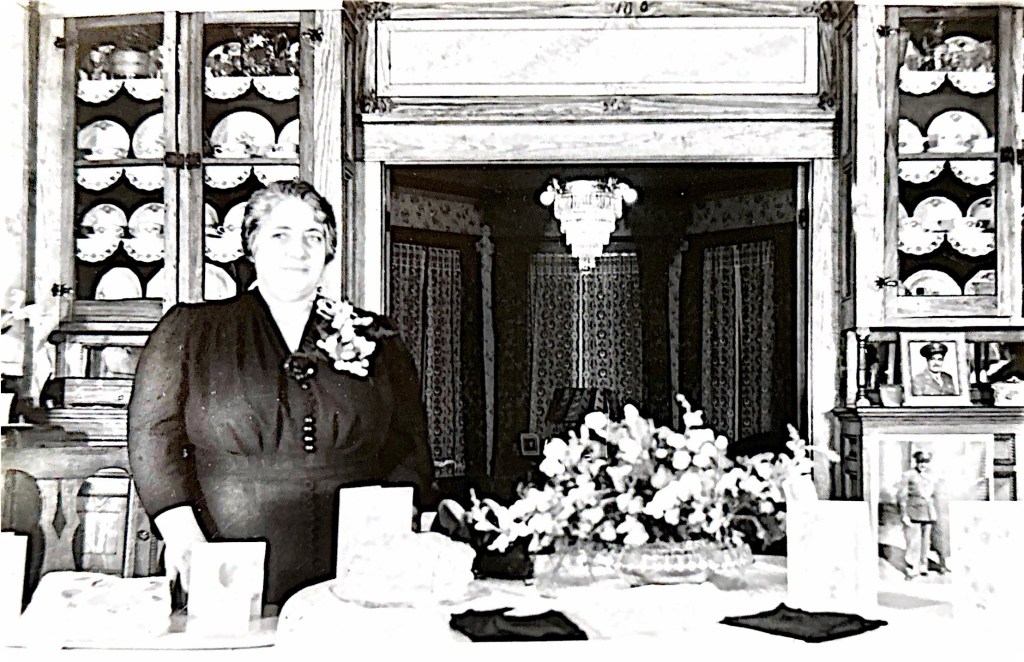

On the day of my brother’s birth, four people were living in Vovó’s house: Vovó, my cousin Violet, my aunt Linda, and Tony, who used to be my aunt’s boyfriend and was now her husband. They had recently gotten married and were living with my grandmother until the new house they were building was ready. It would be a while. The new house was down a country road and up a narrow lane, and Tony was doing much of the work himself. People did that in those days, living with parents after the wedding, and Vovó had plenty of room now that her children were married. I was told to call Tony my uncle, but I still thought of him as my aunt’s boyfriend. The one good thing he did for me was to teach me how to catch a ball. Wait for it, he said, and, just before it gets to you, squeeze it. It worked! I would squeeze and there the ball would be, safe inside my hands. When I say they all lived in my grandmother’s house, I use the word house loosely. Vovó lived in a rented tenement, as most of us did back then. It was a big tenement on a first floor, and unlike my family’s tenement, which was a third-floor converted attic, it had both hot and cold running water, although they didn’t both come out of the same faucet. My mother had arranged to have me stay with my grandmother, her mother, while she was in the hospital waiting for the new baby. Vovó lived close to my school and would have no problem getting me there on time, but she wasn’t good at tying my hair ribbons tight enough. I was not happy about that, but I didn’t complain. I knew that I was a guest and had to be polite.

On the day of my brother’s birth, I pretended to be happy about having a brother instead of a sister. I ate my breakfast, and Vovó walked me to my school. My cousin Violet had to ride a city bus to her school. She had turned sixteen on her last birthday, and she was eager to grow up, leave school behind, and get a job. She lived with our grandmother because she had gotten very sick one day when she was a baby. Vovó, who took care of her in the daytime while her mother, my aunt Mamie, was at work, called the doctor, and the doctor said Don’t move her. So they didn’t. At least that’s the explanation I was given. I wonder now whether the Depression might also have had something to do with it. At any rate Violet lived with Vovó until she got married years later to a man named Tony—another Tony—who played clarinet in a band. He had a daytime job, but the clarinet thing was more exciting.

On the day of my brother’s birth, we all sat around my grandmother’s claw-footed table and had supper, and then Violet went out on a date. I wasn’t sure what a date was, but I knew it involved having a boy come for you in a car. Vovó saw a spattering of raindrops on the window and told Violet to take the guarda-chuva. Violet touched up her lipstick, grabbed the umbrella, and went out the door. After that it was all grown-up talk, and I realized that I missed my mother terribly. Vovó helped me get ready for bed.

On the day of my brother’s birth, I heard loud noises and screams coming from the living room. I had been having a crazy dream about pendulums swinging back and forth, and at first I thought the noises were part of the dream. But I recognized the voices of Vovó, Aunt Linda, Tony, and Violet, and I knew something bad had happened. I walked out of Vovó’s bedroom, and nobody paid any attention to me. Violet was still holding the umbrella, and she looked angry. Vovó was hugging her, helping her unbutton her coat. Aunt Linda was sitting on the floor, leaning against the wall, trying to wedge her feet under the linoleum, while Tony tried to pull her back up into a standing position. What happened? I asked. Nobody answered. Then Vovó told me to go back to bed. Aunt Linda was still working at getting a whole foot, with its shoe on, under the linoleum, which was of course tacked to the hardwood floor. No one would talk to me. So I went back into my grandmother’s bedroom, pulled the loose finial off the bed post, and put it on my head. I wanted to be the queen.

On the day after the day of my brother’s birth, Aunt Linda, who was her normal self again, helped me put all the pieces together in my head. Here’s what happened: Violet’s date dropped her off at the curb and then drove away. As Violet was walking toward the door, a man—a stranger—jumped out of the bushes and tried to grab her. Violet began hitting him with her umbrella, hitting him hard, all the while screaming as loud as she could. She was a loud screamer, and her screams woke any of the neighbors who might have been asleep. But it was still early and probably no one was asleep except me. Violet kept on hitting—it was a big umbrella—and lights came on, people looked out of windows, and the man ran away. Back into the bushes, back into whatever sort of world people like that live in, back away from the safe world of good people celebrating good things like the day of my brother’s birth. When you go out on a date, Aunt Linda said, and she probably even wagged a finger at me although I can’t remember for sure, make sure your date gets out of his car and walks you to your door. I still wasn’t sure what a date was. I still was only five years old. But I would hear that advice often over the years from my aunt and from my mother, whom I still missed terribly and wouldn’t see for a couple more days. Violet didn’t say a lot, though. She was tough and brave.

On the day of my brother’s birth, I learned that good and evil can be so close together that if you squeeze at the wrong time you might get something you don’t want. I learned that gold crowns don’t grow on brass beds. I learned that yes, of course, a girl’s date should walk her to her door, but what if he doesn’t? What if he doesn’t? It would be a long, long time before I went on a date of my own, but I knew what I had to do. Simple enough. Always, whether the sun was smiling like a big yellow omelet or the rain was spitting its anger against the windowpane, I would carry an umbrella. A big one with a long, curved handle. Every time I went on a date. Always.